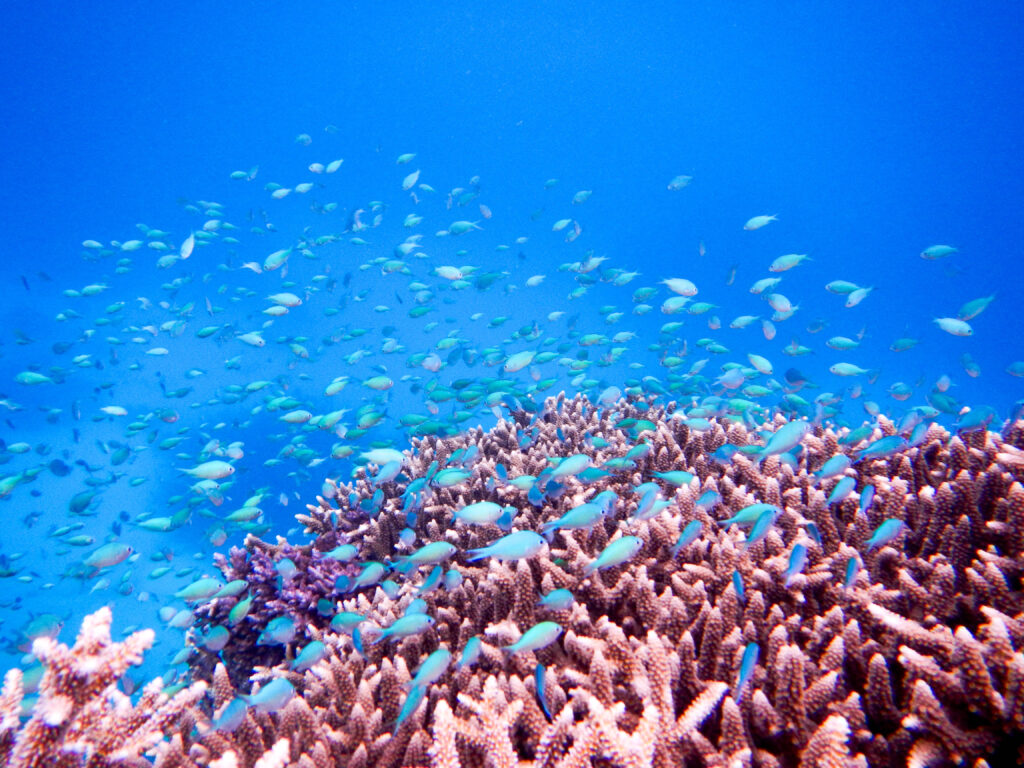

Coral reefs have been described as the canary in the coal mine when it comes to gauging the damage of climate change on the earth’s ecosystems.

Now scientists have discovered a new way to measure their health.

Researchers have found that patterns on the seafloor left by fish grazing behaviours could provide clues about the health of coral reefs which are under threat from warming seas, overfishing and other human activity.

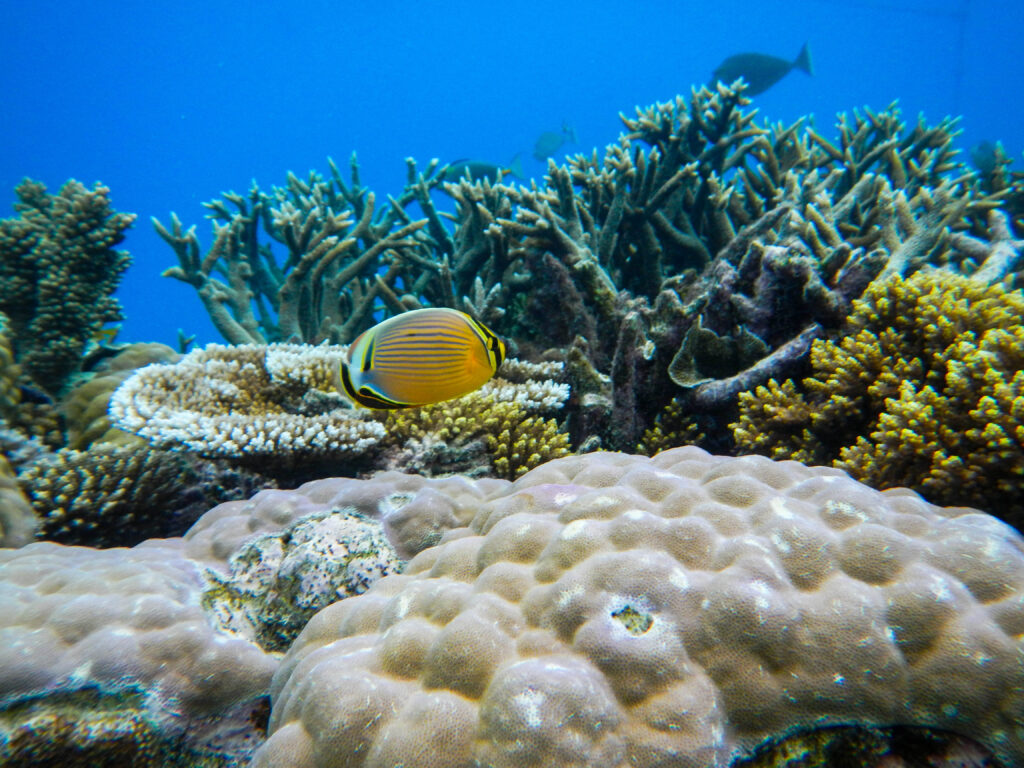

Barren rings of sand that encircle the vivid ecosystem of coral reefs –known as ‘grazing halos’–have long puzzled scientists, who have sought to understand whether the empty patches signify health or decline.

A new study, published in The American Naturalist earlier this month, examined how these halos form when herbivorous fish graze on vegetation surrounding coral patches.

Crucially, the researchers found that the layout of the corals themselves contribute to whether these halos appear. Previously it was thought that herbivores simply grazed closer to coral to avoid predators.

“Having something like this, where you can get a sense of what’s going on–that’s super valuable,” said Dr Lisa McManus, co-author of the study and assistant research professor at the Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology at the University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa.

Using satellite images of Heron Island in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, the team tested two mathematical models to assess how different coral layouts influence the formation of grazing halos. Their findings suggest that shifts in the size, shape or presence of these rings could reflect broader changes in the reef’s food system.

“This is just one tool in your toolkit of the many things you need to measure and pay attention to when you’re trying to evaluate whether your system is doing well or not,” said McManus.

With International Reef Awareness Day coming this Sunday 1 June, the study highlights the potential of satellite technology as a cost-effective, efficient tool for monitoring reef health.

As climate change makes oceans warmer, waters more acidic, and disrupts food chains, scientists say the finding provides a promising new tool for spotting early warning signs of ecological distress in reef systems. This will allow them to have a deeper grasp of the complex dynamics that sustain them.